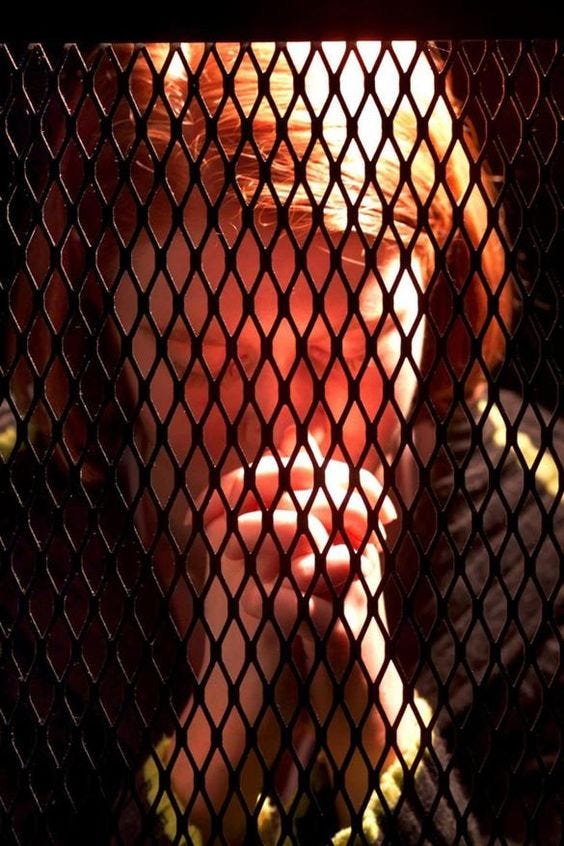

Growing up Roman Catholic, I had to go to confession. It was always a scary but also somewhat entertaining moment. Scary because of the confessional, which always felt like entering a prison cell.

I had no real concept of what I should confess, and I remember making a mental list of things that might count as sins before the priest. As a child and then pre-teen, I struggled to figure out what I should be confessing. The penance given by the priest always seemed punitive, and while I did it (usually something like 50 Hail Marys), I saw no point.

I left the Roman Catholic Church when I was 13. Not necessarily because of confession but because I felt the people I encountered there were oppressive and hypocritical. (I have since changed my mind, but my 13-year-old self saw it this way.)

In my 45 years as an evangelical, I found myself having moments where I wished for a confession. Some sins I had committed made me want to admit to and seek some absolution in the sense of feedback and guidance. I always thought that as an evangelical, I only confess to God, not to some priest (none in evangelicalism). But there was James 5:16: “Therefore confess your sins to one another and pray for one another, so that you may be healed. The prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective.”

So on several occasions, I found myself sharing a sin I considered particularly offensive to God with Christian brothers and sisters in one-on-ones. While that pressure valve allowed me to feel some relief, I never quite felt cleansed.

Fast-forward to January 8, 2023, when Elke was received into the Syriac Orthodox Church by anointing with holy Myron oil. I fully expected to have a one-on-one confession with the priest before I would be received. However, I was told that this type of confession was not necessary, and typically, the faithful pray a prayer before partaking of the Eucharist. In addition, before the Holy Qurobo, Psalm 51 is prayed.

Here is the prayer of confession of sins during the Holy Qurobo:

I make my confession to God the Father Almighty, and to His beloved Son, Jesus Christ, and to the Holy Spirit. I confess the holy faith of the three holy ecumenical councils of Nicaea, Constantinople and Ephesus, trusting in the most noble priesthood ascribed unto you, father priest (Your Eminence), by which, you loosen and bind. I have sinned through all my senses, both inwardly and outwardly in thought, in word and in deed. My sin is great, very great, and I repent of it most sincerely, purposing not to fall again into the same ever. Preferring death rather than embrace sin. Therefore I ask you, by the authority of the sacred priesthood, that you absolve me of my sins, asking god to pardon me through his grace. Amen.

At the end of this prayer, the priest typically asks all to reflect on their sins before God before speaking the prayer of absolution.

I have to admit that this left me a bit disappointed. This was no different from what I did as an evangelical before partaking in the Lord’s Supper. In my husband’s Greek Orthodox church, parishioners regularly go to confession with the parish priest. He offers online times when they can meet with him. When our church got a new priest, I tried again, but I was given a similar answer. I discussed this with a Coptic monk in Germany, Abuna M., whom I had met while doing my PhD research and who was a big part of my spiritual journey to Orthodoxy. He offered to become my confessor. So the next time I was in Germany, I prepared my life confession (I considered it that since I had not confessed since I was 12 or so).

To say it was nerve-wracking is not enough. I didn’t sleep well the night before. There was too much “dirt” to confess for the past almost 50 years. I downloaded a confession app that the Coptic Orthodox Church offers. In it, you step through question after question that lets you think through areas where you may have offended God. It was truly eye-opening to realize how many areas in my life I hadn’t even given a lot of thought to.

The day came, and I met with Abuna M. (in typical monk fashion, he doesn’t like recognition…) in the monastery church. We sat in the back row next to each other, facing forward to the altar area. I was so nervous. Abuna M. began by explaining to me that this was like a doctor’s visit. No doctor seeks to inflict pain on their patient. You go to see them to find relief from your pain. You explain the symptoms, and the doctor can help restore you to full health. And that is how I should view this time with him. He would listen, ask questions where he needed clarification, give me some spiritual help, and pray for absolution from God. The desired outcome was to guide me to spiritual health before God. The mention of the sin was sufficient, not how often, against whom, or any of the detailed information. He would seek clarification if needed. And so I began…haltingly, then more rapidly, and sobbing at some point, overcome by the grief I must have caused God through my careless behavior.

Abuna M., just as promised, gave me calm and kind counsel. He didn’t chide. He didn’t tell me to go pray fifty prayers. What he did instead was to share with me some ways in which I may improve my walk with Christ. He talked of the Christian walk in this life being one of falling, but getting back up and continuing to walk toward Christ. When he prayed over me, I felt such enormous relief. A huge burden had been lifted. A burden I wasn’t even aware I was carrying until that moment. Talk about feeling pure and white as snow! I was living Isaiah 1:18:

“Come now, let us argue it out,

says the Lord:

If your sins are like scarlet,

will they become like snow?

If they are red like crimson,

will they become like wool?”

Abuna M. has become my confessor now - and my spiritual father. He is in Germany, and I am in the United States, but we have found a way to make this work through confession via video call (okay, that still is awkward!) and in person when we can. Most recently, while in Germany, I drove 8 hours to see him do my confession. That is how important it is to me. These confession times with Abuna M. have become an irreplaceable part of my spiritual life.

Yet, this made me wonder why I found it so hard to have my confession heard in the Syriac Orthodox Church. I asked several priests, deacons, and friends in the Syriac Orthodox Church. I had also written about it in my dissertation, but then it was academic, now it was personal. The answers were mixed. Some still had regular confession time with their priests. Others hadn’t been in a long while.

Finally, I reached out to His Eminence Mor Severios Roger Akhrass, Patriarchal Vicar for Syriac Studies, who had provided me with excellent information during my dissertation work previously. He shared with me an article from the Irish Theological Quarterly entitled Penance Rites of the West Syrian Liturgy: Some Liturgical and Theological Implications by Brian Gogan1 and added his own explanation (lightly edited):

The history of the confession in our tradition, as in the Byzantine Church, is not linear. To sum up, in the first five centuries, there was the canonical penitence. It is sometimes called the public confession, because people who had committed more or less great sins, used to participate only in the first part of the Eucharist, while sitting apart.

Confession (or canonical penance) was obligatory for the three great sins (adultery, murder, apostasy). In parallel, there was the practice of manifesting the thoughts to the spiritual father in monastic circles.

For daily "normal" sins, confession was not requested. The Eucharist is given for the forgiveness of sins. But spiritual guidance is always welcomed.

In the Middle Ages (11-12th centuries), the Syriacs, like the Byzantines, adopted a more Western model of confession inspired by the Crusaders.

…

Nonetheless, they made a lengthy ritual and many canons for almost every kind of sin. This became too heavy. People stopped going to communion. And this long ritual was no longer practical. The long ritual was abandoned.

In the 19th/20th centuries, a short prayer of confession with a short absolution was used instead of that ritual.

…

In 1972, the Synod allowed the same short prayers of confession and absolution during the Eucharist for a common confession of the assembly to encourage people to come to communion.

Now, this all made more sense! While the Syriac Orthodox Church never changes in its core Christian teachings, accommodations are sometimes made for the faithful in other parts of the Church’s life. And still, it made me sad that this very healing aspect of Christianity had fallen a bit by the wayside.

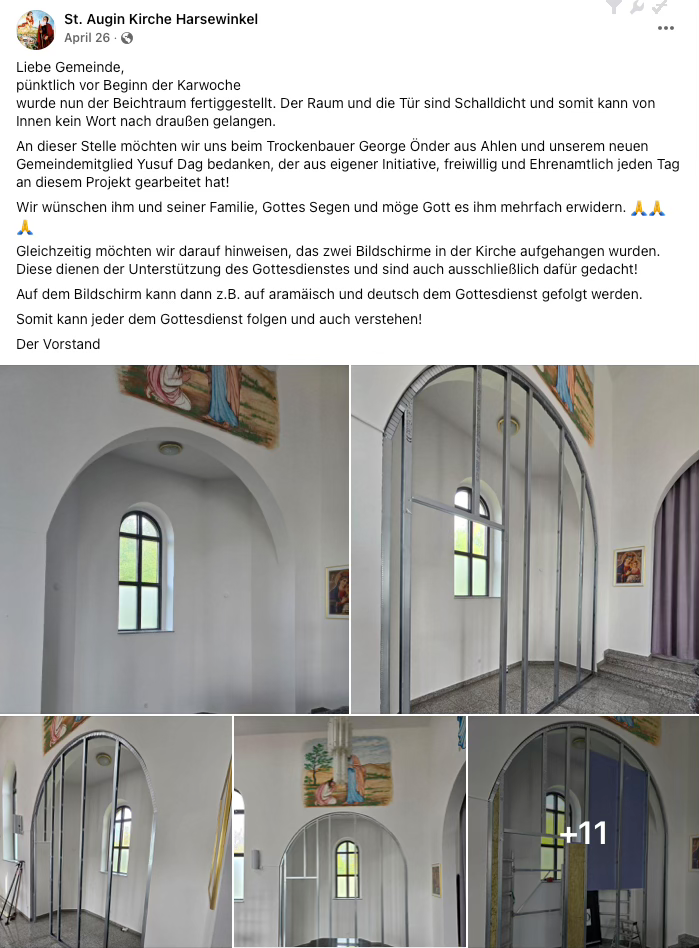

Imagine my great joy when a few months ago, I saw on Facebook that Abuna Amanuel Dag at his church, St. Augin Kirche, in Harsewinkel, Germany, had created a welcoming space where his parishioners can have their confession heard by him. Nothing at all like the confessional I was used to in the Roman Catholic Church, rather a well-lit space, offering privacy while having a one-on-one with the priest. Here is the (German language) Facebook post announcing it.

Now it’s just a door you enter into in the church!

I have to admit that I have a renewed hope that a new generation of Syriac Orthodox faithful will seek confession and find the kind of cleansing my soul experienced from it. 1 John 1:9 says, “If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” God is faithful and just indeed! I have experienced it myself. All glory to His name!

Gogan, Brian. “Penance Rites of the West Syrian Liturgy: Some Liturgical and Theological Implications.” Irish Theological Quarterly 42 (1975): 182 - 196.